PLAYING FOOTSIE ON TOP OF THE TABLE: A CONVERSATION WITH JOSEPH GRIGELY

Jan Estep (New Art Examiner, 2000)

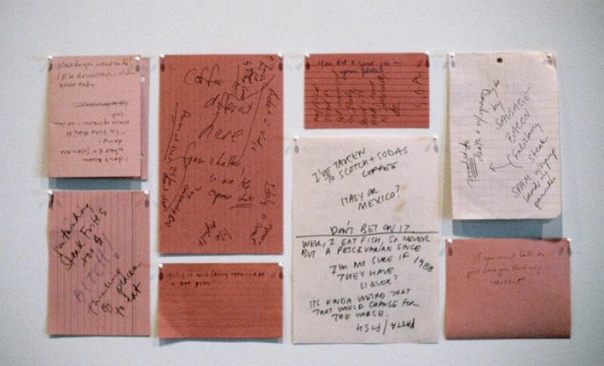

Joseph Grigely’s art conceptually occupies the space between speech and writing, focusing on the gestural elements of communication. One piece in particular illustrates his process: Untitled Conversation (The Panhandler) consists of a sheet of paper with some words scribbled out on it and a small framed text describing the social interaction recorded on the sheet. The text tells a story of a meeting between Grigely, who is deaf, and a man wanting money late one night on a street in New York. Grigely asks people to write out their speech so that he may read what they have to say. The sheet of paper is the man’s attempt to write out what he wanted, but he couldn’t remember how to spell “money” and repeatedly scratched out his attempts; in the end he could not write out his request in words. Grigely has been collecting such written conversations, exhibiting them in tact, building a body of work that revolves around such communicative acts.

Grigely has a Ph.D. in English, has taught history and literature, written critical theory (including the books Textualterity: Art, Theory, and Textual Criticism published in 1995, and Conversation Pieces in 1998), as well as cultivated a career as an artist, exhibiting nationally and internationally. His work was in the 2000 Whitney Biennial. I first met Grigely through my role as coordinator of the 1999 critical studies program at Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, in which he participated. This interview occured via e-mail late this spring.

Jan Estep: How did you lose your hearing? Do you want to tell the story of how you became deaf and at what age? How old were you?

Joseph Grigely: It’s funny you ask because this is something people often want to know but are timid about asking. For good reasons, I suppose, since disability is an evolving condition marked by certain complex events in our lives–events that are both traumatizing and dear to us all at once.

My story is marked by two events: the first was when I was about one year old–I had a fever and it left me deaf in my right ear. My doctors couldn’t quite figure it out since by all accounts a fever like the one I had should have made me deaf in both ears. So I had one more-or-less good ear until I was ten, when the second event occurred: I was playing a game of King on the Mountain with some friends and fell about 15 feet down a small hill. Somewhere on the way down I fell against a tree branch lying on the ground, and a small twig on that branch somehow found its way into my good ear. Poof. Now, I’m pretty much as deaf as a doorknob–as if doorknobs ever could hear.

J.E.: Do you have memory of sounds?

J.G.: Lots of them, actually–the sounds of June 1967, which was the month I became deaf: lawnmowers, barking dogs, and rhythmic voices on television. Remember Schlitz beer commercials (“Schlitz is a light beer, a mellow beer, a hardy beer….”)? Remember Marlboro commercials (the deep gruff voice saying “Come to where the flavor is, come to Marlboro country” and the light feminine voice following up with “filter, flavor, pack, or box.”)? Well, I do.

And there’s the theme song from “Gilligan’s Island,” of course: “A storm came up, the tiny ship was tossed, if not for courage of the fearless crew the Minnow would be lost, the Minnow would be lost”; Gilligan’s whining and excited voice–“SkipperSkipperSkipper.” This is all the sort of stuff filling my head back then–and, unfortunately, still filling it.

J.E.: I know you have an academic background in English literature and have taught as an English professor. How do you teach in the classroom? Could you explain how that works?

J.G.: Well, all of my students at the University of Michigan are hearing–so I always have a sign language interpreter in my classes. I speak for myself, and the interpreters translate to sign language questions, comments, and interjections posed by my students. It works really well–whether for undergraduate lectures or graduate seminars. The difficult part is finding interpreters who can handle Ph.D.-level critical discourse. With a great interpreter, though–and I’ve been very fortunate to have some great ones recently–people forget there’s an interpreter in the classroom. When I do studio visits, though, I usually do these one-on-one: the dynamics involve a very different psychology, and a very different approach.

…

J.E.: You have developed a way to speak with people who do not know sign language, basically by a system of exchanging notes. How do you think the act of writing and reading effects what gets said? Does it make people more self-conscious? Does it give them certain liberties?

J.G.: Well, it’s complicated. Usually I talk with other people, and they will write, so the notes are always notes written by other people. For most people, this is a new experience. Some find it mildly disconcerting; others find it engaging. Ultimately, it’s less about writing than it is about finding another way to talk, finding another way of shaping the spoken word into a material form. Sometimes the words stay on the lines of the paper, sometimes they run off the lines. Sometimes there are gaps, sometimes there are drawings, sometimes there is the unmistakable oddness of ordinariness, as when someone might write “Bye”–or “Sorry, I have to go and pee.” You’d think that it is the weird elaborate academicky stuff that’s interesting, but to me it’s the banal stuff that is–stuff that we say every day, but never write down. This to me marks the difference between writing and talking.

J.E.: And what do you generally talk about in these notes? Do you steer the conversation in any way (in a way that would make “more interesting” art)?

J.G.: No, no, not at all–really, they’re just conversations–sometimes they whisper, sometimes they lie, sometimes they get sexy, sometimes they get ugly–as conversations typically do. Sometimes they go to places spoken conversations don’t typically go–and you never really know in advance where this may be–which is part of the beauty of it all.

J.E.:Do you think there is a difference conceptually in the acts of writing and speaking?

J.G.: A very huge difference. Writing works around certain conventions–as does speaking. A conversation is fundamentally discursive, not linear; there are breaks, sudden turns, lapses. When you read a novel, for example, or a letter–things that are “written”–you know where the beginning is, you know where the middle is, you know where the end is. But with an inscribed conversation–when someone talks on paper–it’s hard to find a beginning or an end. Instead there’s an endless layering of words, marks, and lines.

J.E.: There’s a feeling of chumminess in these notes, like we’re sharing a secret, passing notes back and forth in the back of the classroom. The literal exchange of words (made literal by the writing) feels intimate, like a gift from me to you and from you to me. Have you experienced this in your meetings with people?

J.G.: Sometimes. What’s funny is how other people around us become curious about what we are saying, and how the inability to “overhear” an inscribed conversation has a certain attraction to it. I have one friend who loves to take advantage of this sort of situation when we are among other people. Once, at a highbrow academic dinner when we were seated at a table with a dozen other people, she was talking–on paper–about a pretty wild sexual fantasy–which is sort of like playing footsie on top of the table instead of under it. So, yeah, that’s intimate chumminess for you.

J.E.: There’s also a sense that the language shared takes on a material, physical presence; for example, one night at dinner we were talking and advanced the conversation by writing on a paper table-cloth spread out around us; you could see the path of the conversation traced out along the sheet of paper; arcs, interjections, scribbled-out bits. The conversation made a very fine drawing. There seem to be three ways to go here: Do you look at the collected ephemera in formal terms? Does their significance lie mainly in the content of what gets said? Or is the import primarily in the act of recording these everyday exchanges?

J.G.: Good points here. Fundamentally, I’d say my priority in the middle of a conversation is the conversation itself–what people are saying–simply because all I want to do is “hear” them talk–participate in a social exchange–which is also to say I just want to do what everyone else likes to do.

That the notes could ever be more than records of a conversation is something I discovered quite by accident. For about 20 years I had been throwing them away. Then there was this day in the early 1990s when I had dinner with a friend, and afterwards there were scraps of papers all over the table with fragments of our conversation. They were all disconnected, quite lacking continuity, and somehow more engaging that way, as if they told a story without telling too much. After that dinner I started saving the papers on which people had written until I had a good-sized archive, and one day I spread them on the floor of my studio. I had expected to see a lot of writing, but what I saw instead was a lot of talking. Sometimes there was only one word. Sometimes there were words on top of words. I realized then that these notes were–like the tablecloth you mention–a form of drawing: drawings of conversations.

At first, this seemed a little odd, as if maybe I was pushing the analogy a little too far. But then I considered how we all know what a conversation sounds like–but what does a conversation look like? When you stop and think about it, it’s a pretty engaging question. In England and the lowlands during the late eighteenth century there was a genre of painting known as the “Conversation Piece,” where we can see–through the way bodies are positioned and how they gesticulate-that there is a conversation of some kind taking place. There’s a lot of this in the work of [William] Hogarth, for example, in [Thomas] Gainsborough, and [Thomas] Rowlandson. It’s pretty much a ubiquitous subject matter, one that reminds us that visual arts are not just about the representation of visual experience; they are also about the visual representation of auditory experiences.

J.E.: Some of your shows have a performative component along with prewritten pieces, for example, remnants of conversations held at the night of the opening, comfortable chairs and tables with beer bottles and cigarette butts strewn about. But the work at the Whitney hangs on the wall almost like a painting, with framed passages of text that seem to be written in your own voice. How do you organize your shows and choose which pieces to display? On what bases do you make these decisions? For example, are you democratic about it or decide on formal and/or conceptual criteria?

J.G.: I’m an in-absolute dictator when I install a project–which is also to say: I never really know for sure what I’m going to do in advance–but once I’m in a gallery, I’m determined to get it done in a certain way. It drives curators crazy because they usually want to know very far in advance what I will do–and I’ll reply: Oh, “stuff” I guess.

I learned the value of underplanning at the 1995 Venice Biennale. The “TransCulture” show curated by Fumio Nanjo and Dana Friis-Hansen was at Palazzo Giustinian-Lolin, and using floor plans and photographs I laid out in my studio many of the wall works I intended to show. When I arrived in Venice I was informed I could do whatever I wished to do in my room–but, because the walls were covered with stretched silk brocade, I couldn’t hang anything on the walls! I got around this by using tables and turning the room into a studio–and I was probably better off that way. If you plan too much in advance, you miss the opportunity to work with a space–whether the space is physical or conceptual.

The Whitney was complicated because I wanted to show a new film I made in collaboration with Amy Vogel called Something Say–there’s no spoken or written language in it at all–just a little whistling–but it has everything to do with communication and the language of the body. The Whitney however was adamant I do a wall work–so the piece that went into the exhibition was something I made immediately prior to the show. The nice thing about a situation like this–which is in a way similar to my Venice experience–is that it forces you to respond to the necessary conditions of the situation, and create something you might not otherwise create or do.

J.E.: Have you always been interested in language per se? What is so interesting about it to you?

J.G.: Well, I’m not sure I can explain where my interest in language comes from. Conceptually, it’s infinitely mystifying, either as a formal process, or embodied as literature. But in many ways I find it most engaging as a practical thing: we converse using language, and I love to converse. When I was in fifth grade–just before I became deaf–I had this teacher named Miss Corbett who was–perhaps because of her experience as a WAC [Women’s Airforce Corps] in World War II–a real disciplinarian. She liked quiet classrooms. I liked to talk. So I got in trouble a lot. She’d make me write 500 times in long-hand, “I will not talk in class unless spoken to.” Then–to make things interesting–she’d take up the pile of papers, count them, say thank you, and rip them to shreds. The funny thing is, I sort of miss her, though I’m not quite sure why.

The thing about language I find particularly engaging now is how meaningful it is when inflected by the presence of the person with whom I am talking: how the eyes move, the eyebrow, the hands. This is all part of the experience of a conversation. It’s a very different experience than when communicating by e-mail, for example, or even letters.

J.E.: There was a tremendous difference between talking with you via e-mail before ever meeting you and talking with you afterwards. Over e-mail there’s no way to experience the way your deafness impacts an exchange of words with you; and though some of your personality and style of communicating, even your humor, came across, it helps to have a visual image of you in my mind now when we correspond. The act of “talking with Joseph” entails a wide array of means that is curiously compelling, not to mention entertaining. It makes me think about what else I’m missing.

J.G.: Well, it’s a mutual feeling. The night I first met you at Cranbrook was pretty funny–I thought you were a cleaning lady–then let loose a flustered blush when I realized my mistake–it’s not like I could identify your voice or anything–I like the way that all of this involves a certain kind of ambiguity–uncertainty–if only because it keeps us from getting too comfortable with our assumptions about people and reminds us of the pleasure of surprise.

J.E.: A cleaning lady, jeez! Is that because I had a big bag of groceries for you!? Let me ask another question: You have shown quite a lot in Europe and Japan, among other places. Do you think people in other countries respond differently to your exhibitions than Americans?

J.G.: Yes, though it’s hard to explain this. I think it’s partly because America is fundamentally a monolingual country; people here don’t regularly experience the necessary importance of having to construct linguistic bridges. In Europe you’re constantly communicating from one language to another. You can go 50 miles and all of a sudden you’re listening to Flemish instead of French, or German instead of Flemish, and so I think that in Europe there’s a more considered understanding of the vicissitudes of communicating from one language to another, or from one modality to another.

I also think that in Europe the contemporary art scene is fundamentally different than that in the United States. I find this distinction drawn out both by the art some artists make and curatorial vision. And I also find it in art schools, with their emphasis in the U.S. on classifying work–and the curriculum–on the basis of genres and media. It’s not like this in Europe, at least not in schools like Goldsmiths School of Art in London. I think the break began with [Joseph] Beuys: like [Marcel] Duchamp, he drew attention to ontological issues, and ways in which art involved the exploration of the relationship between material and immaterial values. Here in the States, though, there is more emphasis on the exclusive experience of the material object. Think of American artists who have gone against the grain of this emphasis on objecthood: Lawrence Weiner, James Lee Byars, and Ben Kinmont; they’re much better known in Europe than the U.S. Alternately, the work of many good European artists isn’t appreciated in the U.S. as much as it probably should be: Andreas Slominski, Liam Gillick, and even Douglas Gordon. Sure, a lot of people know who Douglas is, but how many have seen his work? Or how many get to see shows curated by people like Nicolas Bourriaud, Hans-Ulrich Obrist, or Jérôme Sans? All three tend to curate shows that are understated and understating. And all three are unafraid of art that has no precedence as art–something with which few American curators feel comfortable. But I do like the idea of importing these curatorial visions, and seeing how they will affect the development of American aesthetics. Sans has curated some shows in Milwaukee at Inova for Peter Doroshenko, and I think this is terrific.

J.E.: In a performance you and Anne Walsh gave recently at Cranbrook, you carried out a conversation over the phone using a human translator (also on the line with you) and a tele-device for the deaf (TDD) with a liquid-crystal display (LCD); the translator would listen to what Anne said and type it out into written language that you could read. In the live conversation it was very apparent that communication was corrupted in part by the process of its peculiar transmission: things weren’t being translated verbatim and other signs that hearing people take for granted like laughter, hesitations, false starts, and other non-linguistic gestures were not getting across to you via that prompter. I’m curious what you think about these misunderstandings and miscommunications: Do you focus more on what gets across or worry more about what doesn’t get across? In other words, there are always gaps between what people say and what other people hear and/or read.

J.G.: Well, there are always gaps for everyone I suppose–misunderstanding each other is germane to being human. The TDD conversation with Anne worked in a way to amplify the misunderstandings in a weird way: Anne couldn’t read the LCD screen, so she didn’t know for sure how well the TDD relay operator was typing her words. And for my part, I had no idea how well the relay operator was speaking my words. But the audience, who could both hear Anne and see the LCD, was privileged to everything that was happening. It was sort of like Shakespeare’s Comedy of Errors: the players of the stage did not realize the misunderstandings that were taking place–or why–yet the audience could see and understand the misunderstandings, so to speak. It might have been more interesting had I started flirting with Anne to see how she’d respond to my words–spoken by a female relay operator. So in a way, we were only just getting into the process by which communication can be twisted and convoluted by the nature of the process itself.

Which is why, when I’m conversing with someone and they write things down, my focus is not just on the words, or the way they are inscribed, but also on the hand that inscribes them. Often too, when someone writes something on a piece of paper and passes it to me, I like to catch the glimpse in their eye as the paper is passed on to me. It’s a very special moment, for some reason, because of how it privileges the difference in our approach to communicating–plays with it–and tries to find a certain pleasure in it. In this respect, I think my deafness is not so much a disabling condition as much as it is an enabling condition.

I first felt as if the interview was more about Grigely’s deafness than it was about his art, but then I read that him being deaf did connect to part of his work–placing text from written conversations together. Most of the times I look at 3-D art, I think that it’s supposed to represent something, but 90% of the time, I don’t understand it and sometimes feel like the artist is trying to “act” artsy. After reading the article, I did see that there was actual subtext in the written text playing together. Although I was indifferent before reading the interview, now I actually think it’s kind of cool.

I love this idea! I think people get so much enjoyment out of hearing other peoples conversations, now they can read them.

I agree with Travis, it’s like when a teacher grabs a note thats being passed around in class and reads it aloud to the class, everyone wants to know what they were saying.

I would love to converse with this guy… maybe he has instant messenger.

I wish I was deaf, then maybe I would be even a little as cool as he is..

So Joseph Grigley’s work is fun playful secretive… very much taps into former childhood interests and secrecy. The rush of getting away with something dirty right in front of what feels like the parents eyes. I imagine if I was engaged in on of these conversations I would feel liberated to speak of whatever I wanted.